Because the process is so time consuming, tests are 100% of the grade. Homework isn't factored in at all (and my students whined when tests were 50% of the grade in the US!). I think I'm the only teacher at my school who has ever graded homework individually, normally profs just corrected it as a class and maybe give plus or minus 1 point on their test if they did it.

The second trimester is also when most schools have compositions, or cumulative tests for the trimester. Compos, as they're affectionately known, are 50% of the trimester's grade, the other tests make of the second half. So when the end of the trimester came around, I first had to average the two tests I gave before the compo, then average that number with the score they earned on the compo. Last year, I would do everything in Excel, then copy into the bulletins (report cards). This year, I've realized that Excel actually takes more time than just using a calculator and entering it directly into the bulletins.

So I repeated that process exactly 161 times. The French, English, and Biology teachers teach in every class in the school, so they had to do this about 350 times. Less than fun. After all the teachers are done filling in their subjects, the Professeurs Principals (PP) have to add the Notes Ponderees and calculate the trimester average for one class. I'm PP for 5e (the lovely class pictured in my previous post), and in addition to calculating the trimester average for each student, I have to calculate the class average and determine the rank of each student. Not hard, but time consuming.

|

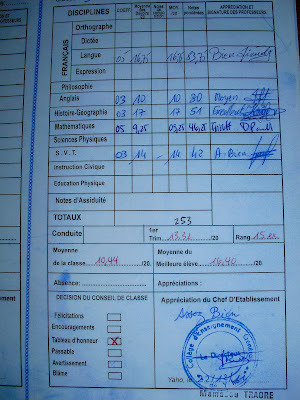

| A completed bulletin from the first trimester. The class average was passing, but barely. This trimester, the average wasn't passing... :( |

So this trimester, my classes grades were a little disappointing. The class average was 9.6 out of 20. Not so hot. Of the 85 students, only about 35 passed. Of the 32 girls, only 7 passed. 7! I actually had a long discussion with the other profs about why girls seem to do so much worse. No one had any good answers, but it was nice to hear them acknowledge the discrepancy between boys and girls. I think a big reason for the drop in grades (for all students) were the compos. The compos are all done over a two days, meaning that half of their entire trimester comes down to those two days. If they're even just a little off, or a little nervous, they can easily ruin their whole trimester. Not an ideal system.

You'll also notice that next to their signature, each professor gives the student an appreciation, which is just a quick one or two word remark on the students work. There are standard responses we give for each grade the student achieved. For low grades, 0 up to 10, the comments are Null, Very Weak, Weak, Insufficient, then Average. If the student earned 10 or higher we have Average, Good Enough, Good, Very Good, and Excellent. Not really all that encouraging in my opinion...

I feel that this blog became a little more technical than I intended, but hopefully it gives a little insight into the amount of time that goes into tasks we have long since simplified using technology back home!